A Life with Others

An Imagined Retrospective

Born in 1944, Salzmann grew up a transitional era of documentary’s evolution. Following the First World War, documentary had become a staple element of mass media in the United States, filling weekly picture magazines and proliferating in a modified form as journalism in the daily press. The rhetoric of showing social “fact” was embraced across the spectrum of political perspective and institutional authority, not least by many agencies of the US government during the Depression—most famously the Farm Security Administration, which launched the careers of several of the most important photographers of the era. In the aftermath of the Second World War, documentary in the US became roughly synonymous with visual humanism, or more precisely, visual humanism girded by official confidence in a bettering world. Documentary addressed the cultures of loss, survival and rebuilding after the war, and showed the redevelopment of an enlightened capitalist culture whose dominant truths were predicated upon scientific advancement, mass communication, and a developed conception of public service.

With Salzmann, there is an open question about how he came to find his way into documentary thinking, and how he came to register his own sense of himself within it. There is a further question about what came to characterize his way, his method, his style. Some part of the answer might reside in Salzmann’s direct teachers, in particular Reuben Goldberg (1906-1960), chief photographer of the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology from 1937 to 1960.

A suggested design for the Introduction…

Images included in the introduction…

Laurence Salzmann, La Vendange (The grape harvest), near to Bordeaux, France, 1964

Luis' Family

Single Room Occupancy (S.R.O.)

Tlaxcalan Sketches

City / 2

La Laie / Bath Scenes

La Lucha / The Struggle (Print: 42x42'')

Rittenhouse (Print: 42x42'')

Misk'i Kachi (Print: 42x42'')

Last Jews of Rădăuți

Amintire din Tlmpul Trecut / Remembrance of a Past Time

Vents

Jerusalem's People in Public

Mioritza

Anyos Munchos i Buenos / Good Years and Many More

Face to Face: Encounters Between Jews & Blacks

De Noche / The Night

Echele Ganas

Misk'i Kachi Runakuna / Sweet Salt People (Print: 36x24'' to be mounted on gatorboard)

Abstracts: Garip

Abstracts

Abstracts: Reflections

Click an image above to go to it’s Series within the larger exhibit,

or below you can pick a section of the exhibit to explore further.

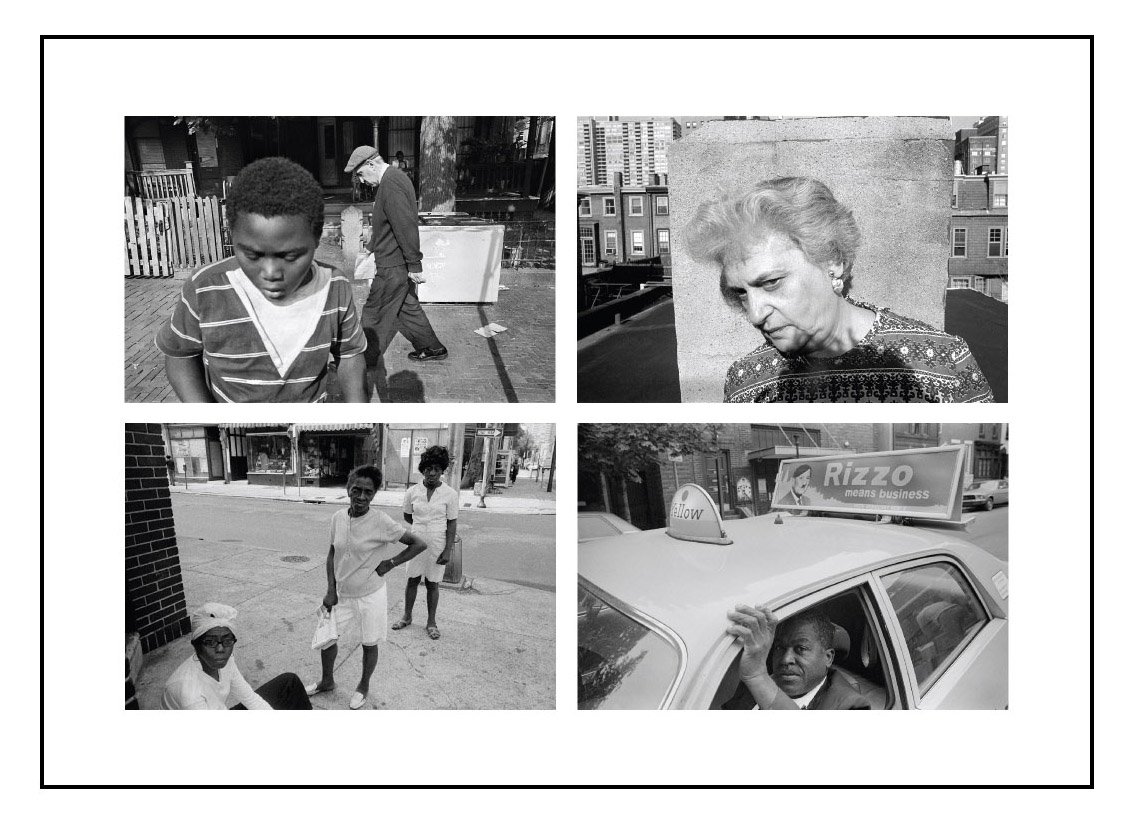

City / 2

In 1971, Salzmann participated in an exhibition at the Philadelphia Museum of Art on the nature of public space in the city. The theme was timely: the previous decade had seen seismic political and cultural shifts, from the Civil Rights movement to the anti–Vietnam War movement, to the feminist movement, plus the emergence of youth countercultures, not to mention race riots in many cities—all of which played themselves out very publicly, claiming and reclaiming the public realm as the space of debate, denunciation, repair and transformation.

Amintire din Tlmpul Trecut

Remembrance of a Past Time

In 1974–76, during the years that he was living in Rădăuţi, Romania, Salzmann would from time to time make trips to Bucharest, the country’s capital, and other Romanian cities. His work

in the city is immediately distinguishable from his work in the town, turning from the personal and intra-communal to the urban and the anonymous. Almost all of his work in Bucharest occurs in public places, under the sign of a type of artistic idling, or purposive loitering—I might call it “luftmenscherie,” to make up a word by crashing the Yiddish “luftmensch” (free spirit, drifting wisdom-lover, sometimes occupationless) and the French “flânerie” (leisurely sauntering, walking connoisseurship of the street).

Vents

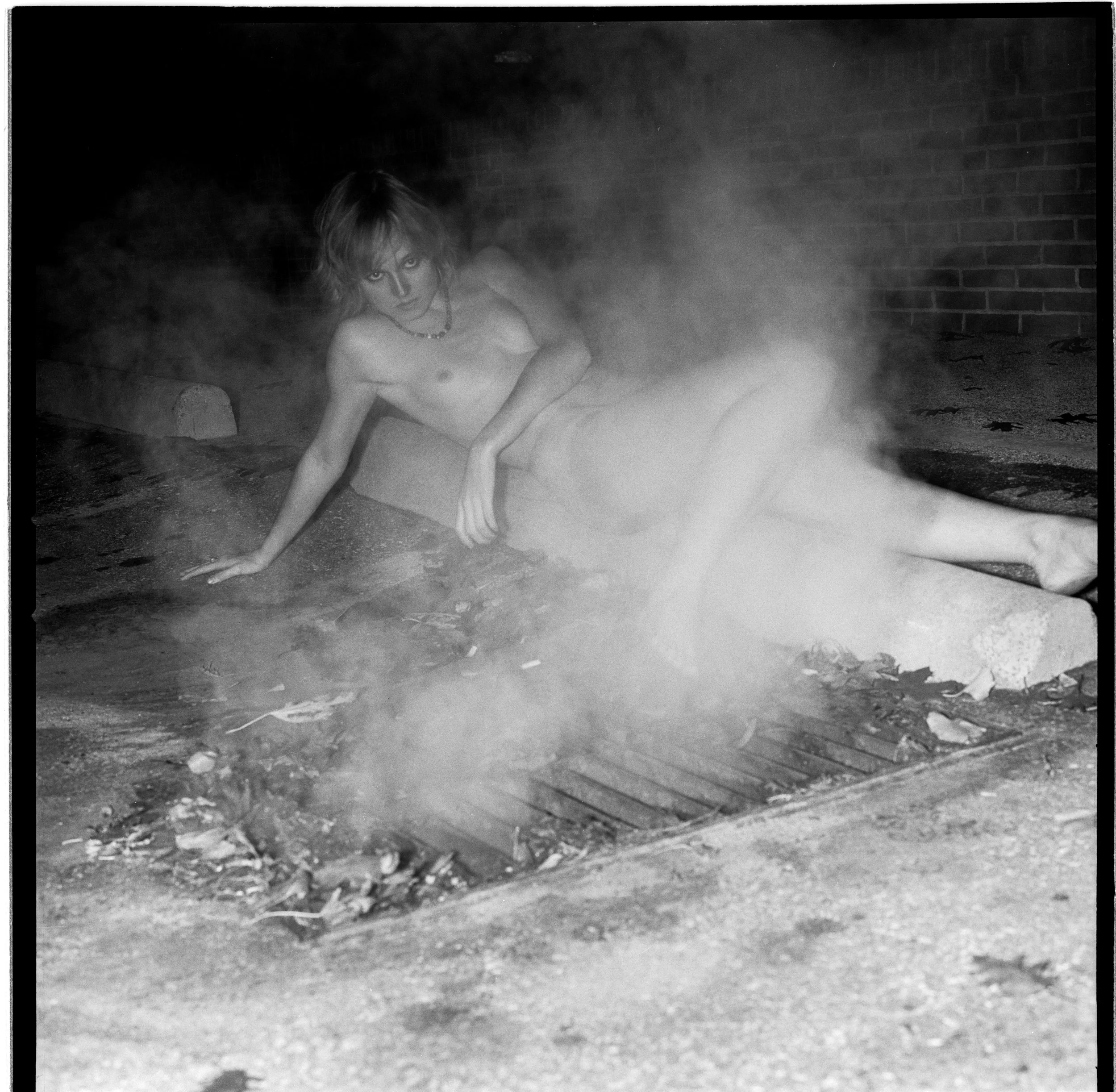

In the early 1980s, a new stream of experimentation emerged in Salzmann’s practice. For some years Salzmann had occasionally made studies of nude models, mostly women, and mostly in private settings. Unusually for Salzmann, whose work typically assumes “project” form rather quickly, these photographs read as somewhat marooned in the archive, never collected together and never acquiring artistic momentum between one another. Sometimes these photographs have a distinctly mischievous quality.

La Baie / Bath Scenes

While living in Rădăuţi, Romania in 1974–1976, Salzmann frequented the town’s Jewish bathhouse, which doubled as a place of ritual observance—it held the community’s mikvah— and also a place of recreation, general health and community. The entire Jewish community used it, women and men alike, and indeed the whole town, Jewish and non-Jewish alike—as all over Europe, in a time when hot running water was uncommon, and the bathhouse was a place to clean, to socialize, to get warm in winter, to relax, to escape.

La Lucha / The Struggle

In November 1999, while walking in the city of Santiago de Cuba, Salzmann happened across a humble neighborhood gym named for the Cuban Olympian Aurelio Janet. Peering through the doorway, he glimpsed young athletes, and discovered that it offered after-school training in weight lifting and Greco-Roman wrestling for boys aged 8–18. He walked in, introduced himself, and began to ask questions about what was going on. He was invited to make pictures, and over the next four years, returned half a dozen times to photograph the young wrestlers.

Imagining Cutumba

Between 1999 and 2002, in multiple visits to Santiago de Cuba, Salzmann found himself photographing not only the wrestlers and weight lifters of the Aurelio Janet gym, but also the Ballet Folklórico Cutumba, one of the country’s oldest and best-regarded folkloric dance companies. Its repertoire focuses on Afro-Cuban traditions specific to the eastern part of the country, mostly derived from the religious and social dances of Haitian immigrants—cultural forms that are exotic even to many Cubans. Salzmann, in other words, zeroed in on the very heart of the debate over what Cubans call “Cubanidad” (“Cubanness”). For a century, Cuban intellectuals, artists and eventually revolutionaries have framed Cuban identity in terms of cultural fusion and syncretism, expressed as the hybrid culture of an “Afro-Latin nation.”

Abstracts

By the mid-2010s, Salzmann had developed a daily practice of photographing that saw the withdrawal of the human figure altogether—or nearly so (partially returning in an overtly notional form). Made in streets, forests, building interiors, and just about anywhere, these pictures eventually made their way into loose collections under the titles “Transient Diamonds,” “Site Unseen,” “Fictive Archaeologies,” “Coral,” “Aegean Blue,” “Lamed Vavniks,” and “Reflections.” Many hundreds of such pictures exist in Salzmann’s archive, forming a vibrant and unruly chapter of the later years of his artistic life.

Misk’i Kachi / Sweet Salt

Forty kilometers north of Cuzco in Peru’s Sacred Valley, near the town of Maras, are a complex of salt ponds that have been producing salt since pre-Inca times. Salt and mineral-rich subterranean streams are channeled into hundreds of ponds on terraced hillsides, where the mountain air evaporates the water, leaving salt crystals to be harvested by hand. Salzmann found himself captivated by the sight and history of the ponds, which became one of the key subjects of his Fulbright fellowship to Peru in 2016. His initial interest was the persistence of pre-Columbian lifeways in contemporary Andean culture, for which the salt ponds provided a rich source.

Luis’ Family

In 1966, Salzmann was invited to train for the Peace Corps at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque. His training included immersive courses in Spanish, plus an “in-country experience” in which he was taken to Ciudad Juárez, Mexico. He was assigned to live with a family of adobe brick makers, migrants from the Mexican state of Zacatecas, who resided in a shantytown (barrio humilde) outside Juárez, near the Rio Grande river. Salzmann began to photograph them while their guest.

Single Room Occupancy (S.R.O.)

In 1968, St. Luke’s Hospital Department of Community Psychiatry hired Salzmann to work on its Single Room Occupancy project on New York’s Upper West Side. The project’s purpose concerned unattached single people clustered in urban rooming houses, what was termed at the time a “Community of the Alone.” Broadly, the project’s goals were qualitative: to help create and sustain a positive self-image and feeling of mutual care among SRO residents, to further residents’ willingness to seek outside assistance, and to improve the hospital’s own ability to address the needs of these people.

Last Jews of Radauti

A Fulbright grant in 1974–1976 permitted Salzmann to spend two years living in Romania, originally to study ethnic Romanian folk culture. In an introductory tour of the country, he received a recommendation to visit the southern Bukovina town of Rădăuţi, well known for its open-air peasant market and near several monasteries renowned for their paintings. He traveled to Rădăuţi, arriving on a Saturday, not knowing the peasant market was held each Friday. He wandered into the large synagogue just beside the main square, to find nine men gathered, unable to begin public prayers. Salzmann became the tenth man.

Mioritza

In 1981, Salzmann arrived in the village of Poinana Sibilui in the Transylvania region of Romania, with a burgeoning interest in animal husbandry, specifically transhumance—the seasonal walking of livestock between grazing grounds. Transhuman shepherding is an ancient tradition across the world, at least a thousand years old in Romania, and is an occupation—for example, cowboys in the American West—perched midway between intense work and pastoral wandering.

Anyos Munchos i Buenos

Good Years and Many More

In 1984, Salzmann received a letter from Turkey’s Chief Rabbi David Asseo, at the urging of the Beth Hatefutsoth Museum in Tel Aviv (“The Diaspora House,” formerly the Nahum Goldmann Museum of the Jewish Diaspora). Asseo and Beth Hatefutsoth invited Salzmann to create a photographic record of Jewish monuments remaining in Turkey, to supplement the museum’s already existing archive of the material traces of Jewish life around the world.

Face to Face:

Encounters Between Jews & Blacks

In the early 1990s, Salzmann turned his attention to the intercommunal history between Jews and African Americans in the United States, picking up a topic that was at the center of his work twenty years earlier, in City / 2. An initial version of the new work was a collaboration with Salzmann’s lifelong friend, the Philadelphia photographer Don Camp, resulting in a 1994 exhibition at the National Museum of American Jewish History in Philadelphia, in conjunction with the exhibition “Bridges and Boundaries” being shown at the African American Museum in Philadelphia. In 1995 Salzmann published his own work for the project as a book and film titled Face to Face: Encounters between Jews & Blacks.

Echele Ganas /

Do Your Best

In the early 2000s, Salzmann came to know a group of Mexican immigrants to Philadelphia from Sierra Norte de Puebla, a rugged mountainous region in the northern part of the Mexican state of Puebla. Most of them were manual laborers, some skilled and some unskilled, who had come to the US without documentation, committed to some number of years of intensive work and communal living, in order to be able to send money back home while saving everything they could, with the intention of returning with the means to build a more prosperous life in Mexico after some years. Salzmann became interested in the life they left behind, and between 2005 and 2008, made several trips to the home villages in Sierra Norte of his friends in Philadelphia.

Misk’i Kachi Runakuna

Sweet Salt People

In 2014, Salzmann began traveling to the Andes, first to La Paz, Bolivia, and then to Cusco, Peru, and further into the Sacred Valley of the Inca. Much as he did with his interests in Romania in the 1970s, he received a Fulbright fellowship to spend a year in 2016–2017 studying traditional folkways in Peru. He returned for prolonged trips each subsequent year through 2020. And much as in the 1970s, folkloric research served as a point of artistic departure and return—for straying across the boundaries between art and document. As so often before, his deeper purposes emerged when he allowed himself to wander from his starting purposes, which is one of several qualities that I would call the hallmark of a good artist. And as before, Salzmann received new opportunities as a means also of reaching back to refine old ones.

Additional Bodies of Work that could be included in the exhibit.

Possible designs for an exhibition of the show…

Introduction

Section A - Part 1

Section A - Part 2

Section B - Part 1

Section B - Part 2

Photographs by Laurence Salzmann

Texts by Jason Francisco

Possible Show Designs by Aki Shigemori

Photo Editing by W. Keith McManus

Web Presentation by James T. Rowland